The process industry (food & beverage, liquids, sheet goods, solid & fluid packaging operations) differs from the parts manufacturing and assembly industry, where the Lean, 6 Sigma and Theory of Constraints methodologies were developed.

The unique characteristics of supply chains in the process industry make them less responsive to a one-size-fits-all approach. Performance optimisation in the process industry requires a customised approach.

There are 3 things to consider when modifying the “Big3” improvement methodologies for the process industry;

- The structural differences

- The good

- The not so good

The Structural Differences

At the macro level there are 5 main differences between the process industry and the parts assembly industry that effect the way an improvement methodology should be designed and implemented (see 7 fundamental differences between food & beverage factories and car factories for a more detailed comparison);

- Labour Percentage – Using round numbers, in the parts manufacturing and assembly industry, labour is 70% of the factory cost; material and capital form the other 30%.In process industries, the ratios are reversed. Labour represents approximately 30% of the cost of manufacturing; capital and materials represent the other 70%.¹This puts a heavy burden on management in the process industry to ensure that Continuous Improvement initiatives utilise labour more effectively and convert directly to the bottom line.

- Waste Accumulation – the manufacturing process in parts manufacturing and assembly often has many small and separate steps resulting in small accumulations of inventory, transport, or other forms of waste between the steps.Automated lines in the process industry rarely have discontinuities that cause uncontrolled accumulations of material between steps. Waste accumulation in the process industry usually takes the form of stand-by labour or capital.

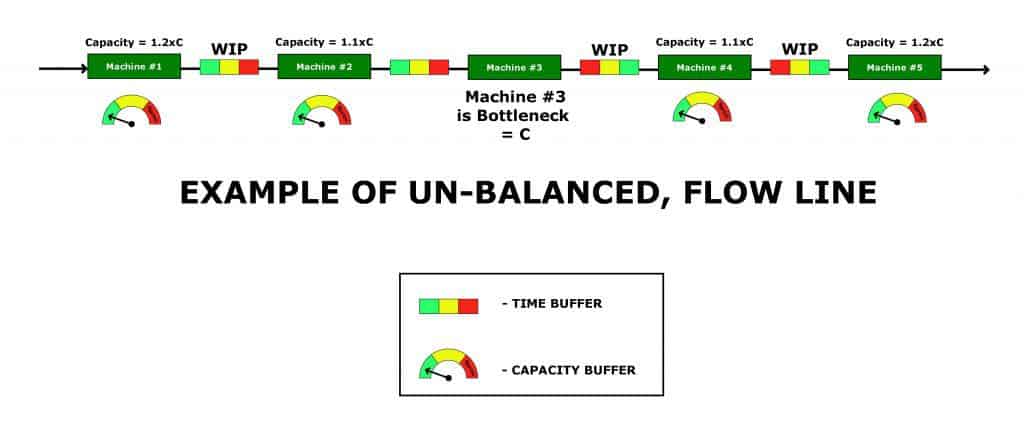

- Line Design – In the parts manufacturing and assembly industry manufacturing lines can be balanced using labour. If there is a short term capacity mismatch caused by breakdown losses then workstation capacities can be adjusted by adding labour or other resources.High-tech processing lines rarely have this flexing capability and so automatic managed buffers are used to absorb downtime losses which creates un-balanced flow lines (see What is a flow line and how can it be manipulated to maximise performance? for more information on un-balance flow lines).Un-balanced flow lines have an upper threshold of performance which is determined more by the statistical interplay of machine capability and managed buffers and less by crewing and training.

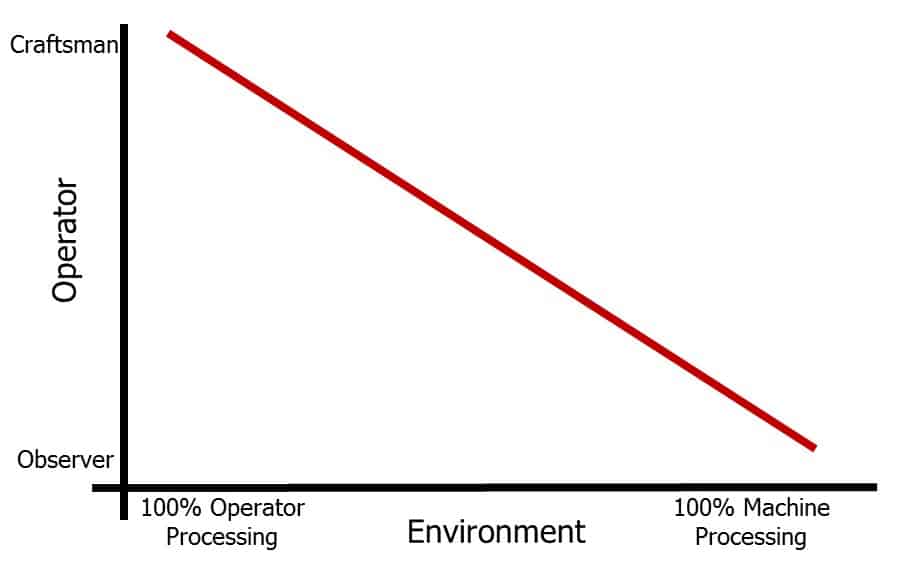

- Operator interaction – Operators in the parts manufacturing and assembly industry interact with the product on a much more intimate level. Product quality and production capacity are influenced more by their training and the way they manage their resources. They are more craftsmen than observers.Operators in the process industry have a very limited ability to interact with the product. While they can influence the performance of machinery using their knowledge, their role is more observer than craftsman.

- CI resource & training strategy – The small flexible accumulations in parts manufacturing and assembly environments alert operators or managers to the presence of small problems to their operation. Enabling many people to address many small problems is a powerful force multiplier and general Continuous Improvement (CI) training can create a powerful virtuous circle.The statistical, high-technology, capital intensive nature of processing environments makes the efficacy of general CI training less influential on the bottom-line. CI training can establish a sound base of knowledge although that knowledge most be directed in a forensic way. Therefore the CI resource and training strategy for the process industry contains many more subject matter experts, individual contributors, mentors, technologists and analysts.

The Good

The Big 3 improvement programs; Lean, 6 Sigma, and Theory of Constraints are applicable to the process industry with some modification and nurturing.

See these articles for more information on the applicability of the tools from each program;

- Lean tools and their applicability to the process industry

- 6 Sigma tools and their applicability to the process industry

- Theory of Constraints (TOC) tools and their applicability to the process industry

It is GOOD to have consistent approach to Continuous Improvement although its not important to align yourself with just one approach. In fact each of the Big 3 has a particular focus;

- Lean – common sense tools for waste removal

- 6 Sigma – technical tools for variability reduction

- TOC – common sense and technical tools for bottleneck removal and system optimisation

A customised Continuous Improvement program that cherry-picks the best of the Big 3, selected on the basis of the unique needs of your operating environment, is the best way to go. This is particularly true for the process industry.

Setting up a Continuous Improvement program for the process industry is good for 5 reasons;

- Culture – most operators in the process industry are observers, see above, and lets face it this can be boring! Creating a culture of improvement using an overarching program is helpful in creating employee engagement, demonstrating that the business is interested in improving work environments and offering employees a way of engaging with the broader business.

- System – labour percentages in the process industry are much lower than the parts manufacturing and assembly business so creating a systematic and efficient way of driving Continuous Improvement through precious and limited resources is worthwhile.

- Training – all of the Big 3 tools can be supported by structured training programs although, for the process industry, tools must be selected wisely (see links above) and training should incorporate a strategy for subject matter experts, individual contributors, mentors, technologists and analysts.

- Common language – the names of most of the tools used in the Big 3 improvement programs are widely used throughout manufacturing industry. So sticking with these tools helps to promote a common language, makes the skills transferable across business units and helps with the credibility of the improvement effort.

- Spring board – creating the Continuous Improvement program with all the systems, procedures and training creates a springboard for many future change initiatives that need to be introduced to a production platform. It offers a ready-made sytem for disseminating and receiving information, distributing training, and eliciting operator engagement during projects.

But there are 5 vital ingredients that are missing from standard Continuous Improvement packages, which leads us into the not so good.

The Not So Good

There are some not so good aspects of packaged improvement programs and 5 of these are particularly true for the process industry;

- Lack of priority – none of the Big3 programs offer much help when it comes to the Industrial Engineering and Operations Research techniques needed to assign priorities to improvement activities. This is a particular issue for high-tech, capital intensive processes where priorities can be masked by the statistical interplay of capacities, buffers and product design.

- Lack of focus (or the folly of busy-ness) – There are many targets in a manufacturing environment. Sometimes Continuous Improvement programs become a way of efficiently overloading resources, particularly in the process industry where the resource pool is smaller.A lack of focus causes a lot of multi-tasking which is inefficient and can affect improvement program credibility. In some cases an over-commitment to one improvement tool can lock out progress on other, often more important activities (this is particularly true of 5S programs).

- Lack of return – how often do you here the phrase “the benefits of our Continuous Improvement program are over the long term, therefore it’s hard to attach a value to the P&L statement”. Every activity should either have some link to good governance (hygiene, safety, environment, etc) or it should have a clear link to business cash flow or customer service.

- The dreaded business model – most businesses that deliver packaged improvement methodologies are built around a training model where economies of scale are achieved by delivering the same training package repeatedly.Some provide a slight variation on this theme where all problems need to fit into the standard approach to problem identification and resolution (eg. some bottleneck approaches). This one-size fits all approach can be inadequate in the process industry where the solution must be more customised.

- The manufacturing centric – the Big3 programs were all designed with the broader supply chain in mind and this is particularly true of Theory of Constraints. Implementation of Continuous Improvement programs however, is rarely done with the total supply chain benefits in mind. Often the overarching goal is to make products go faster without a clear understanding of how this benefits the rest of the supply chain, if at all.

¹ – Liquid Lean, developing Lean culture in the process industries: Floyd, Raymond C. Taylor & Francis Group 2010.